In this long-term comparative research project, I am interested in how state-driven family separation policies are remembered. I am (slowly, due the pandemic) in the process of conducting field research in Canada, Australia, the US, Germany and the UK, bit by bit visiting important memory sites, reviewing documents and media coverage, and interviewing.

In early 2020, I hosted a workshop on “Remembering Children” at Nottingham Trent University, which resulted in the publication of a special issue of Jeunesse. This volume includes an article that raises some of the issues I am grappling with.

Book project: Grave Pedagogies: The Memory of Family Separation in Comparative Perspective

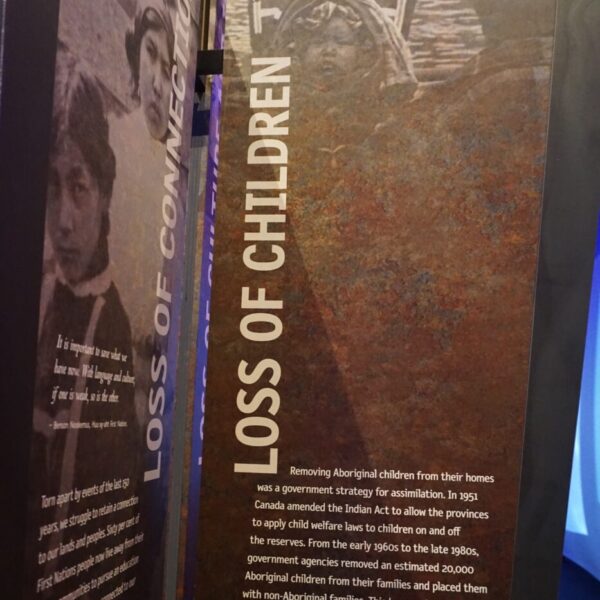

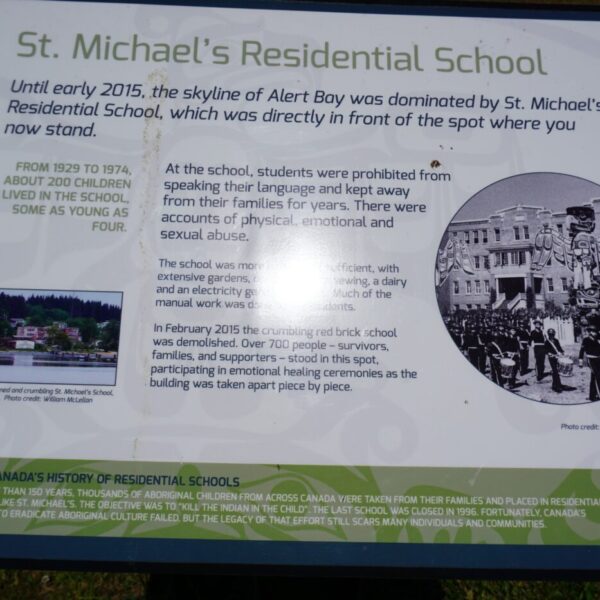

The history of child separation policies is the last two centuries is varied and tragic. In the workhouses and Magdalen Laundries of 19th and 20th century, the poor and “fallen women” were separated from their offspring, partly so that children would not be “infected” with the disease of poverty and immorality. Child migrant schemes during roughly the same time period took poor or orphaned children away from their familiar surroundings and shipped them off to far flung colonies. In Australia, these kids came to be known as “Forgotten Australians.” They were often placed together with Aboriginal children who had been forcibly taken from their parents. In Canada and the United States, Indigenous families were torn apart in an effort to “breed the Indian out of the child” – a policy that lasted over 100 years and has been acknowledged as cultural genocide by the Canadian government. These children were housed in Boarding or Residential Schools, similar in their design and treatment of minors. In the US, the racism inherent in these measures had its precedent in centuries of slavery – one of the most insidious aspects of which was the routine separation of enslaved families. In much different settings, the dictatorial regimes in Argentina, Spain and East Germany pursued – partly clandestine, partly officially sanctioned – policies of removing the children of dissidents. In the GDR, as in West Germany, state welfare provision for children was shaped by National Socialist ideas about childrearing and premised on the merciless authority of adults. They led to horrendous practices of physical, emotional, and sexual abuse that bear a striking resemblance to those witnessed in many other instances of child removal into state institutions.

The justifications of these practices by authorities across the globe – whether based on pedagogical, religious, ideological, or colonial principles – were remarkably similar. A central objective of my work is to understand these principles and practices and how they are directly or indirectly linked across borders and eras. Another key goal of my research is to trace the processes of reckoning with child removal and institutional abuse, which has recently begun, despite the differing cultural and historical contexts. Survivors have come forward, publishing accounts and producing art to “work through” their trauma. Along with the rising sense of injustice, loss and anger, survivors continue to grapple with the shame of having been in state “care”, of not having had “normal” families. High rates of mental health concerns, substance abuse, and domestic violence among victims are the result. These enduring legacies and stigmas suggest that societies have not fully dismantled the policies of the past, and enduring prejudices continue to shape contemporary attitudes toward families.

However, we have also seen collective campaigns for justice and memory. Activists have demanded the marking of former children’s homes, boarding schools, and camps as “sites of conscience” that must be officially acknowledged by the state. And we have seen commissions of inquiry, compensation schemes, apologies, and other official responses. As a result, a topography of memory concerning institutional abuse is emerging in various countries: memorials, markers, and museums that recall the plight of separated children and their families. This developing memorial landscape provides an opportunity for societies to confront their complex and painful history.